What follows are some informal posts I wrote for a blog I once kept when I was in my twenties and finding my way in life during the years following the Great Recession in Seattle, Washington, USA.

Doomed Love Between Redheads

February 19, 2011 – A scene at Cafe Solstice in the University District

Curly-haired redhead lass comes in and sits at Solstice’s second largest table on a Saturday, tan skirt made of wispy fabric, ugly thigh-length sweater with a fake gold belt buckled over it. Big, black, frumpy purse. Burberry scarf. Grey tights. Ankle-high brown leather boots. She walks up to the counter, buys two coffees, sits back down, and writes something in Sharpie marker on the cups. She draws a heart under each message she writes, sets the cups side by side, takes a picture with her phone, texts it to someone, then waits. And waits. AND waits!

Her nose is a little masculine, but it looks good on her. It is made femininely sexy by a rhinestone piercing. She has gold drop earrings, and bobby pins clip back her side-parted hair. She is getting antsy. Every time the door opens, she looks up, then back down at the cups in disappointment. She starts drawing koala bears on napkins. Then checks her phone. Then cranes her neck to look out the window. Then touches her hair to make sure it’s still in place. Then goes back to drawing koala bears.

At long last, her man arrives. He looks exactly like her, but bearded. His sweater looks like his grandma knitted it, with brown deer silhouettes and red diamonds sandwiched between horizontal brown zig-zags. He sits, and the girl leans into him, trailing her fingers insecurely, possessively over his leg. He fails to notice the message and heart she drew on his cup. She tries to indirectly guide him to look, but fails, and so has to point it out to him overtly, killing the spontaneous cuteness of it all. The moment is painfully awkward. He tries to salvage it by toasting his paper cup to hers. The light weight of her cup against the full heaviness of his is a marker of just how long she had to sit waiting for him.

Would Malcolm Gladwell give them six months? A year?

The Old Man from Sverdlovsk

January 30, 2011

Last week I went down to the U-District one morning at about 9AM. I was walking down University Way when I saw this old man I’ve seen a bazillion times before. He lives in the U-District. I know this because he almost stepped on me once coming out of his apartment building. (I was sitting on the stoop waiting for a friend I was meeting.) I have known for some time that the old man is Russian because I’ve heard him arguing with employees at Magus Books over the prices on used books in Russian. He wears a long dress coat and a grey Breton cap, which together make him look as if he stepped right out of the 1970s USSR. His coat is tan and a little dirty, and he has at least one hearing aid. His nose hairs are long and his teeth are kind of ground down, maybe even rotting a little. I get the impression that he is kind of a pest for local merchants, but I find him fascinating. He’s like a character out of a Samuel Beckett story!

I had never talked to him before, but I had always watched him whenever I’ve had the chance. I’ve noticed that he’s very friendly, talking to strangers on the street all the time. He knows a few words of Chinese and Spanish, so if he meets someone who speaks these languages he tries his phrases out on them. I’ve wanted to talk to him myself, but I’ve been hesitant, in part due to shyness, and in part because I’m not confident he’s entirely sane. But after once again overhearing one of his arguments with a Magus cashier, I vowed I would talk to the man the next time I saw him.

And so it went like this: He was standing on the sidewalk in front of the UW bookstore, squinting at a handwritten sign taped to a lamppost. He seemed to really want to know what the sign said, but he appeared baffled by the script in which it was written. I hesitated, then walked up to him.

“It’s Korean, sir.”

He looked at me, and said, “What language is this? I can’t understand it.”

“It’s Korean, sir.”

Then he asked me what country I come from. I told him, “This one. But I’m from a different state. Colorado.”

He scratched at the stubble on his chin and said, “Ah, yes, Boulder, Rocky Mountains, very nice. Yes, but what country do your parents come from?”

“This one,” I told him.

“Yes, but what country did your great grandparents come from?”

I began listing my putative ancestry. Irish, Scottish, German, Dutch, blah blah blah, plus a tribal ID card from the Cherokee Nation that I don’t dare show anyone in a place like Seattle. Then I asked him which country he comes from, even though I already had a pretty good idea.

“I am from Soviet Union,” he said.

“Ohhhhhh… Uh, which city?” I asked.

“Ah, you know Soviet Union geography!” he said, quite pleased, even though I had exhibited no proof of such knowledge. “I come from Urals,” he said.

“Oh, near Yekaterinburg?” I asked.

“No, Sverdlovsk,” he said.

Ah. Yes. The nature of this man’s eccentricity was becoming clear. Yekaterinburg was called Sverdlovsk during the Soviet era. I told him that I was studying Russian, and he insisted that I tell him all the Russian words I know.

“Chelovek. Koshka. Spahseebuh,” I listed. (Person. Cat. Thanks.)

“Ah yes. Spahseebuh, thank you very much,” he said. He then asked me how I learn Russian. I told him that I learn from books, and that I have met a few people from Russia who help me.

“You mean people from Soviet Union.”

“Uh… yes, people from the Soviet Union,” I corrected.

He then asked me to tell him which cities they all come from, so I listed their cities of origin, making sure to say “Leningrad” and not “St. Petersburg,” and ending with, “And I also have a friend who, like you, is from Yek… I mean… Sverdlovsk.” At this point, he insisted on writing his name and phone number down for me.

“Give my phone number to your friend who is from Urals. He is my countryman, he must call me.”

I could only stutter my reply, already regretting what I’d signed my pal up for. “Uh-h-h-h-h, I don’t know when I’ll see him again, but I’ll try to remember to bring your phone number to him.”

We then spent a few minutes talking about Russian authors. He informed me that he likes Pushkin, “classic Soviet authors like Gorky,” and some other names that he mumbled incoherently. Then he shook my hand, reminded me again to give his number to my friend from the Urals, and we went our separate ways.

Uncle Walrus and the Aspenites

September 28, 2010 – written while staying with my father in Parachute, Colorado for a month while I studied for United States Foreign Services Officer Test

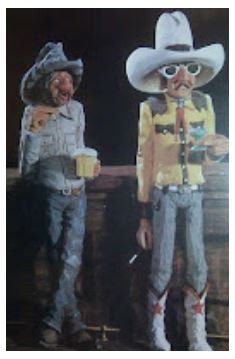

When I was a kid, my mom had this picture on her office wall:

A caption below the picture read: “I see by your outfit that you are a cowboy.”

That picture epitomizes a cultural disconnect that happens here in “The Valley,” and it goes deeper than just the debate over who is or isn’t an authentic cowboy. The Valley encompasses a large part of Garfield, Pitkin, and Eagle counties—the areas east to west along I-70 and northwest to southeast along State Highway 82. In the west along I-70, you have blue-collar towns like Parachute, Rifle, Silt, and New Castle. The farther east you go on I-70, the wealthier the towns become. Glenwood Springs is a middle-class town with upper-class aspirations. Still farther east is Vail, a wealthy ski resort town. Southeast of Glenwood Springs on Highway 82 are Aspen and Snowmass, where movie stars and wealthy people from all over the world have summer or winter mansions. The Valley’s blue-collar workers—a mix of poor and lower middle-class whites and Latino immigrants—commute over an hour each day to build those mansions. For twenty years my father was among them, until he started finding smaller projects to work on for his fellow church members in the Parachute area. When I was growing up he did drywall work on mansions for Miami Vice’s Don Johnson, Arnold Schwarzenegger’s financial advisor, and a Saudi prince. It was common for my dad to come home with tales of seeing people like Goldie Hawn and Kurt Russell walking around towns in the wealthy end of The Valley. Ask my father about these people, and he will tell you that the only thing that motivates them is outdoing their neighbors in displays of status. It’s great job security for the blue-collar workers, because when one movie star builds a gigantic mansion, the neighbor across the street has to tear down their own mansion and build an even bigger one, just to compete.

My father often recounts a time when he had just finished creating the final texture on the plaster of a wealthy man’s house. The house was built in some sort of avant-garde design, and, at the man’s request, my father had mixed metallic flakes into the plaster to give the impression of gilded walls when the sun shone through the windows. Once the plaster job was finished my father overheard the homeowner talking to himself, saying, “I do believe I’ve got something here that no one else has.”

The disconnect is both cultural and economic. Those who live in Aspen, Snowmass, and Vail are lumped together as “Aspenites” by the blue-collar workers. Aspenites are reported to look down on the blue-collar workers who commute so far to build their fancy homes and clean their houses. Here are the types of people that get labeled as Aspenites: The wealthy, especially those who are not Colorado natives. LGBTQ individuals, especially the flamboyant ones. Movie stars. People who ride horses with English saddles while wearing jodhpurs. Skiers. People who buy organic groceries. Democrats. People who watch soccer games on TV. People who drive compact cars. People who are against gun ownership. People who recycle. City folk.

What makes the blue-collar people living in the west end of The Valley different from the Aspenites? They shop at Walmart, not necessarily because they like Walmart, but because it’s affordable. They watch NASCAR, American football, or bull riding on TV. They drive pickup trucks—some old, others gigantic and souped-up. Their hands have calluses. Their bodies are often overweight or falling apart. The artwork in their homes depicts quaint farm, hunting, and cowboy scenes.

Now, allow me to introduce my Uncle Walrus, a blue-collar worker living in Silt, Colorado, but originally from Broken Arrow, Oklahoma. My brother and I call him Uncle Walrus because every year at Thanksgiving he overeats and then stretches out on his back on the floor with his mountain of a belly rising and falling as he snores in a big post-turkey nap. His belly and mustache make him look like a walrus sunning itself on a beach. He is a retired Army man. He used to give my brother and me coins from all the countries in which he had been stationed: Somalia, Haiti, Germany, Panama, South Korea. He retired from the Army when I was eleven years old and came to live with us in Silt for a while. I remember that he used to spend his free time during that first year of retirement watching endless cooking shows on satellite TV. He never cooked anything, he just watched the shows.

Uncle Walrus now works as a plumber all over The Valley. He’s worked for the same company for years and he makes decent money doing it. Last week he told us some of his work stories over Friday Night All-You-Can-Eat fried catfish at Vance Johnson’s Outlaw Ribbs in Parachute. I stealthily turned my digital recorder on. I’ve transcribed my favorite tale he told to illustrate the way blue-collar workers perceive Aspenites.

Background information: This is a story about a house in which Uncle Walrus is currently renovating the plumbing. Imagine him telling it in his unhurried and earthy Oklahoma accent:

“This architect built his own house. He’s GAY. He’s got a boyfriend AND he’s MARRIED, and you see pictures of them all around the house with all THREE of them in the picture. And the housekeeper lives there, and I said, ‘You know, I feel sorry for the wife,’ and she goes, ‘Oh, SHE knew what she was gettin’ into, don’t feel SORRY for her.’ She [the wife] just comes and stays at Christmas for a week. HE comes two or three or four times a year. She only comes once. He’s a huge architect, she’s some kind of a fashion designer, and…it’s crazy. This house has got I don’t know how many rooms. There’s twelve bathrooms, and it’s a real weird design. It’s on the side of the mountain. It’s a cir..not really a circle driveway. You drive in and you can drive under the house. When you drive under there’s bedrooms above you, but over here on the ground level there’s nothing but the garage. And then… it’s just… he’s one of these that… all this WEIRD art. And I am NOT into WEIRD art. Like in one room it looks like they took tinfoil, like twenty feet… or… ten feet wide. And they just kind of krinkled it all up. Then they splashed some green paint on it, and they put a sheet of GLASS over it. And it’s weird, when the sun comes in it bounces off this one wall and turns that tinfoil pink. And…everything in the REST of the house… there’s a picture, like from that window to the other side of that window, and THAT tall, of an ALLIGATOR with whipped cream all over it…a LIVE alligator. And, you know, then there’s a picture of a bunch of Navy guys standin’ here in their dress white uniforms. They all got a real serious look on their faces, and, before I knew he was gay, I asked the housekeeper, I said, ‘What’s that all about?’ and she said, ‘Aw, it’s a GAY thing,’ and I said, ‘Whaddya mean GAY?’ and she goes, ‘You see the picture there of the three of them? Well, there you are.’”

This clash of cultures has become newly fascinating to me. I was raised by The Valley’s blue-collar workers, but the life I’ve lived for the past eight years in Seattle makes me look more like an Aspenite-in-the-making in my family’s eyes. (You know, because I recycle and use canvas grocery bags.) I see the beauty and flaws in both worlds. I often feel the frustration of being stuck between them, though maybe that position is a gift. Maybe it makes me a cultural ambassador between the two. Or maybe it’s more like being stuck in cultural purgatory…